Not even halfway up the chairlift my face was already red from the beaming morning rays. Dirt was beginning to trace the ditches between the moguls under the lift. It snowed only two days before, now it was 70 degrees and any semblance of winter has subsided. Two days after and the snow flew again, rejuvenating whatever was left of the season.

Terry Peak in Lead, South Dakota raised me. From the first time my dad took me to the slopes at age two until purchasing my 19th season pass this year, it’s all I’ve known. I was barely old enough to see out the window when 12-foot snowbanks would enclose the road up to the lodge. The bartender working at the Dark Horse would let me sit with my dad. The sign directly above my head stating “21 and older only.” That same sign was situated above my head this year when I purchased my first PBR.

The chairlift ride in the morning is part of my work routine. Until this year, I always refused to work at Terry, fearing it would pollute my love for skiing with resentment for work. That fear never came to fruition.

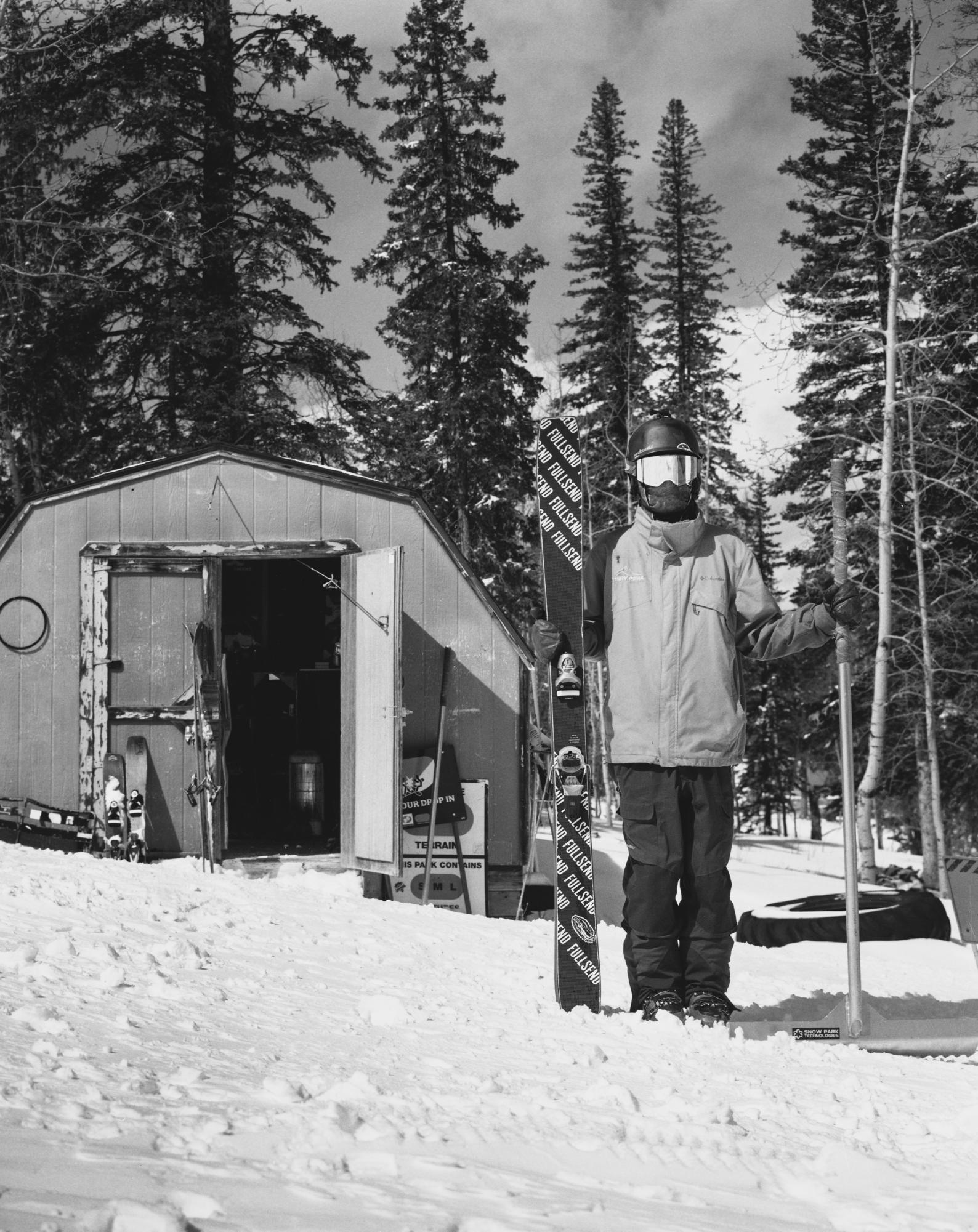

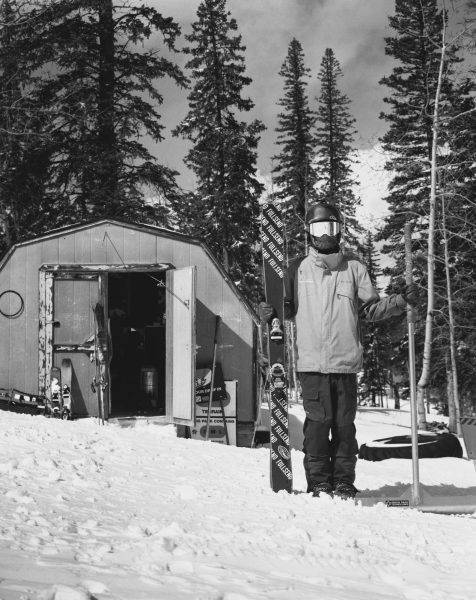

The rest of the morning routine consists of drilling holes and setting up safety signs. I work in the terrain park, a shining example of the ups and downs of Terry Peak the last 10 years. After drilling in the last sign, I walked up to our homebase. An old blue shed with rental snowboards drilled into the walls and ceiling, acting as insulation. We have a diesel heater, but it doesn’t work. Two shitty space heaters are plugged in next to the outlet. Powered by a 400 foot extension cord leading to the snow-cat garage. A pile of cigarette butts is already forming in the snow outside the door.

“I literally got kicked off this mountain like four times,” said Derek Ayala, a veteran snowmaker and park crew worker. “I come up here, try to poach and Timmy Leopard, the old snowmaker, would catch me, everytime. I got blacklisted for a couple years.”

Ayala is the quintessential park crew attendant, spending his early years poaching runs and being a nuisance to management, all while training with hopes of being sponsored. The days of sponsorship are long gone now, but like so many others at Terry Peak, his legacy is now being passed down to his son.

“Im actually just going to be a coach at this point,” Ayala said. “I lost my knee so I’m not trying to push myself as much as I did, definitely starting to feel my age.”

Minutes later Ayala did a backflip on the first jump in front of the shed, making me question where this age is that he’s talking about.

“It’s the dream dude, it literally is the dream,” said Blade Cox, another local snowboard bum. “Even in my mid 30’s it’s something that I’m really passionate about and will continue to be until I’m old. Even when I can’t ride, I’ll still be at the bottom of the hill, stoked for all the kids.”

Cox and Ayala are part of a dying breed of ski-bum, both originally learning how to board at another local ski area, Deer Mountain. “America’s best kept secret,” the Deer Mountain’s billboard says.

The ski resort was taken private a few years ago, making it the best kept secret for only the uber wealthy. “The billionaires are moving to Bozeman so the millionaires are moving to Spearfish,” is a phrase becoming more true day-by-day.

“It was free, you know, you could just go ride and a lot of the locals would show up there,” Cox said. “Deer Mountain is what I call my home mountain.”

I called Deer Mountain, renamed Deer Mountain Village, to inquire about a day pass or visiting to see the changes.

“Call back when you can afford a home,” the phone operator said.

The privatization of Deer Mountain is just another ski resort on the list of prioritizing profits over customer experience. Vail Resorts alone has acquired over 40 ski resorts in the last 20 years, causing lift-tickets and season passes to skyrocket across the industry. Unless, of course, one purchases an Ikon pass, granting the owner access to all Vail-owned properties.

“Are you Ikon people?” asked a lady sitting across from me at the bar, implying that owning an Ikon pass is now a sub-culture.

Vail and other conglomerates are leading a shift in ski culture from being one with nature and a grounded, local experience to more closely resembling a commercialized trip to an amusement park. It’s only a matter of time before a suit with deep pockets comes knocking on Terry Peak’s door.

“I think we’re two very different demographics,” said Landin Burke, the current terrain park manager. “And if nothing else I think all of our local legends down at the Dark Horse will scare off any of those suits. I kind of welcome a little bit of competition.”

On the day of Burke’s high school graduation, Timmy, the same one who blacklisted Ayala from the mountain, walked up to Burke after the ceremony.

Burke had no plans after college, Timmy gave him the opportunity to come work for him in the park. Since that day Burke is a consistent sight in the park, raking the takeoffs at the end of every day. Even he will admit he never expected to work in the park beyond that first season. Now, seven years later, the park is alive because of him.

“The only reason I’m here is because of Landin,” Ayala said. “He is the park, he took the reins. The people I work with are the only reason I’m here.”

“The only reason I’m here is because of Landin,” Ayala said. “He is the park, he took the reins. The people I work with are the only reason I’m here.”

Smoke rose from Ayala’s mouth as his cigarette burned down to the filter. He flicked it to the ground, adding to the ever-growing pile. Another local skis up to the shed, the fifth one that day, looking for conversation and a place to chill.

A continuous strand of people begin hitting the box rail in front of the shed before popping out of their bindings and hiking back up, just to hit the box again. This goes on for hours, encouraging cheers are silenced by body slams on the box and winces of pain. The shit-talking is just as apparent as the bruises forming on thighs and shoulders.

“That’s what we do it for,” Burke said. “Being out here, posted up, somebody stops by that you haven’t seen in a while. It’s like ‘Oh my god, it’s my buddy from Wyoming I haven’t seen in two years.’”

Like me, Burke was raised by Terry Peak. This year was his 23rd owning a season pass. He was originally taught by his father before he followed his brother into the terrain park and never looked back.

Burke admired the park crew, idolizing them as the best and most creative skiers on the mountain. His brother was one of them, as well as Ayala and Cox. Now, young skiers look up to him for advice, the same way he viewed the older generation.

“It’s kind of all I’ve ever known to some extent,” Burke said. “It’s not really a job, it’s not really a sport, it’s definitely a lifestyle.”

That lifestyle used to be integral at Terry Peak through freestyle events put on every year. Drawing in crowds of hundreds to watch the locals compete for prizes and glory.

“Terry Peak, I don’t believe has ever fully supported terrain park culture,” said Jenny Ringling, a previous terrain park manager at Terry Peak, starting in 2009. “It’s kind of like skate parks, skate rats, it’s just this taboo saying of they’re just out there doing hoodrat shit.”

Park culture is closely tied to skate culture and all the stereotypes that come with it. A place where social-rejects, alcoholics and drug addicts reside. When in reality, it’s where the next generation of Terry Peak regulars are being trained. They are given a space not only to train, but a place to hangout and feel accepted.

“I don’t think Terry Peak is supporting it at all,” Ringling said. “I think they just tolerate it.”

Ringling was able to build the park up to over 20 features, small, medium and large jump lines and a full halfpipe. Multiple severe injuries that year put park growth on a hold and began a slow decline in size and support.

“I try to be the rebel, but I also understand from their side that the park is a big liability,” Burke said. “I think we got swept under the rug for a while and I’m just trying to bring it back and get a little more support.”

Nowadays, the park takes up half the run and has a wide variety of features, thanks to Burke and his efforts to keep it alive and return to the glory days.

Burke was shown a video well before starting his first year in the terrain park which showcased changes coming to the mountain. Some of the changes included moving the terrain park to the beginner hill right in front of the main lodge and building a new lodge on the other side of the resort. None of which have happened.

“We’ve been stagnant for a really long time,” Burke said. “There was a comical video about Terry Peaks 20 year grand vision, not a single step on that video has been completed.”

Terry Peak is Burke’s home, Ayala’s home, and my home. Giving Ayala a place to bond with his son, teach him everything he knows and give him the same life-changing experiences he himself experienced at the same age. Allowing Burke to continue his mission to bring the park back to the glory it held years ago while training the next generation of park rats.

“Maybe some kid is out riding by himself and you say ‘hey, hi, how’s it going’ and go do a chairlap with him,” Burke said. “Maybe hold their hand the first time they try a rail and they’re like, ‘Oh my god I get it,’ it’s the little things like that.”

I was that kid out riding by themself, too scared to try a rail and too awkward to ask for help. Burke changed that and helped me overcome that fear as he has for countless others for numerous years.

“You know the park used to have a name back when it was cool and respected,” Burke said. “Area ‘76.”