Just northeast of Sturgis, South Dakota, nestled right outside of Bear Butte National Park resides Bear Butte Gardens. This farm has become a staple of the organic produce market in the Black Hills area. The company was founded in 2010, and as of 2012, Michelle Grosik, the owner, had the farm officially organic certified.

“I was growing vegetables,” Grosek said. “I just wanted to have my hands in the soil and grow something. I realized that in the area there were a lot of backyard gardeners, but there weren’t a lot of people right around Sturgis that were growing vegetables to sell to friends and neighbors. That’s why I started with them because I could’ve easily gone to flowers, but I felt that vegetables were a greater need at the time.”

Grosek truly seemed to want to help better her community and provide healthy options for locals.

“My goal is making sure that the local community has access to locally-grown, fresh and nutritionally dense food,” Grosek said. “We want to help people understand the true seasonality of food unlike how some supermarkets and grocery stores may have all types of produce throughout the entire year.”

To support this concept of seasonality, along with the natural flow of how crops grow locally, Grosek relies on local businesses and even neighbors to demonstrate how weather and seasonal conditions can affect the outcome of certain crops.

“We rotate through collaborating companies with the time of the year,” Grosek said. “Our popular items really just depend on what’s the most abundant during different parts of the year. A couple years ago we were able to get our hands on a mountain of asparagus, and then last year we had a neighbor that would bring us apples every morning to sell or turn into apple chips.”

A portion of their stock is collected from these local businesses and families for a variety of different products.

“We have about 60-plus producers that we buy from,” Grosek said. “There’s meats and wines and beers from local companies. Also tea mixes and similar things.”

Although the farm collaborates with other organizations in the region, Bear Butte Gardens has grown, raised, processed and sold the majority of their product itself.

“I have chefs and bakers that come in to make products,” Grosek said. “They sell across the board: salsas, pickles, pasta sauces and we make those in our commercial kitchen. We also process and dry all of our herbs and such in the starter greenhouse during the winter, then we sell and use them for the stand.”

When asked how the farm keeps their practices sustainable, Grosek had a take that allowed for freedom within her trade.

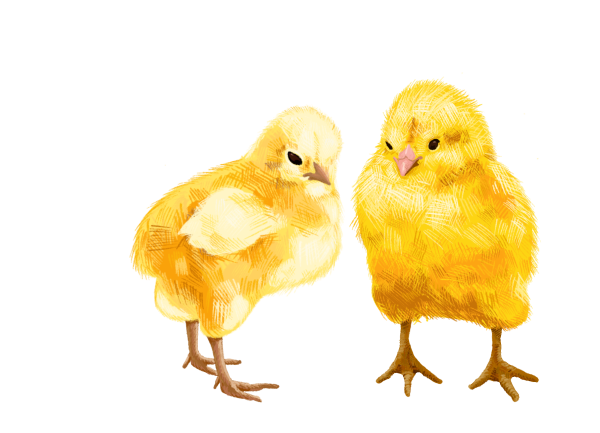

“[Sustainibility] is a word that is used a lot anymore, so it has a lot of meanings, and I feel like it’s a bit overused,” Grosek said. “Even with that though, to live up to our definition of sustainable or self-sustaining, we do a lot of things. We butcher the poultry on the farm. We compost the feathers, keep the chicken feet. We use everything except the heads and guts. We send our cattle to a butcher and we get as much back from that as we can. We send the skins off to get tanned, and try to get back as much organ material as possible. We also get the bones and fat back since those can be used for so many different things.”

Bear Butte Gardens also takes these practices into account with her crops and raising the animals as well.

“We grow our own hay to feed to [our livestock] and have pasture for them to eat and try to bring in the least stuff possible from off of the farm,” Grosek said. “We’re not there a hundred percent. We still sometimes have to bring in a few dumptrucks full of manure from someone else to have a big enough compost pile to handle all of our gardens, but we also use our old hay to give more carbon to our compost so we don’t have to buy rotted hay from other farmers when we can just rot our own. Then it makes it easier because we know exactly what’s in that hay instead of having to ask that question to the people we’re buying from.”

Being an organic certified farm, there are many restrictions and guidelines that Bear Butte must live up to so it can continue its certification.

“Our seeds need to be certified organic or saved from our farm or another that is using organic practices, then be able to prove that,” Grosek said. “If for some reason I can’t find certified organic, I then have to track that I wasn’t able to find them, and find the next best option for that particular crop. Another example, would be our tractor, if we were to take it over to a neighbor’s place, when we bring it back we need to wash the wheels and any implements on it. Say we maybe cut some hay for them and they’re spraying [pesticides or fertilizers] over there, then we have to wash that tractor so we’re not bringing anything back to our farm that could contaminate the soil.”

This also requires Bear Butte Gardens to find alternative methods of maintaining its land through the use of livestock.

“When we decided to do organic certification, and we realized that if we didn’t want to spray some sort of fertilizer on our crops, then we needed to have some sort of nutrition for the soil to not use up the nutrients,” Grosek said. “We thought we probably needed to have something that was producing manure and do some composting, and have some control over what we’re putting on our gardens. We started with chickens, then we added on turkeys, then lambs, then we added cattle and goats. What animals we have just depends on the year.”

Grosek also considers her honeybees to be an extension of her livestock. Keeping such delicate insects leads to an abundance of preparation.

”For their best health you need something blooming from March, ideally, to October or November,” Grosek said. “We’re constantly planning things to bloom at different times. It’s not just for our honeybees though. Once you have honeybees, you become very aware of all the other pollinators too because honeybees are really the one pollinator [we have] that aren’t native at all. We do a lot of work to have healthy land here for [all of the local pollinators].”

”For their best health you need something blooming from March, ideally, to October or November,” Grosek said. “We’re constantly planning things to bloom at different times. It’s not just for our honeybees though. Once you have honeybees, you become very aware of all the other pollinators too because honeybees are really the one pollinator [we have] that aren’t native at all. We do a lot of work to have healthy land here for [all of the local pollinators].”

These livestock have also extended their opportunities for events to be held through the company.

“We’re thinking of doing a fiber festival later in the fall [of 2024],” Grosek said. “Our sheep need to be sheared twice a year, so we’re thinking of doing a demo with our Icelandics. Then we want to do some sort of a meal [focused] around lamb specifically, then invite some people to do some more demos like how to spin wool into useable fiber.”

Bear Butte Gardens supports a host of other events through collaborations with other local companies.

“We have a Mushroom Festival that’ll be on July thirteenth, and this will be our second time doing this [event],” Grosek said. “It surrounds everything having to do with mushrooms and we’re working with Black Hills Mushrooms in Rapid City for it. [The festival is about] growing them, foraging for them in the hills [and] cooking with them.”

Not only does the farm host large scale events, but it also hosts smaller scale cooking classes and private dinners.

“Typically we have classes in the kitchen two to three times a month. They’re open to the public and cover a lot of different things. Our chefs do kitchen skills classes which include knife handling, vinegrettes, pasta-making, canning, so many different things,” Grosek said. “We also do farm-to-table dinners. The chef makes dishes with several meat options, then we have local wine and veggies. Our strong suite is probably doing meals that are completely local.”

These events include planning and community support to help reach their long-term goals.

“It’s a lot of talking and a lot of planning,” Grosek said. “If we realize we’re having conversations about the same projects over and over again, at some point I’ll say, ‘Okay, let’s sit down, write these down and prioritize them for the next one, two, three or even five years.’ We’ve found it’s easier to do it backwards.

“We start with our five-year plan then work our way into the one-year plan, but we do spend just a lot of time talking and not really having too much organization to it all, and that’s good too. We get the neighbors opinions about projects or [family members] just trying to get input about what we should do next.”

The immense amount of work put into maintaining something leads to a very meticulous, but fulfilling career.

“Doing these things, [being environmentally conscious and maintaining organic status], makes your eyes open up to every single thing we’re doing here, and if it’s harmful or beneficial to the land,” Grosek said. “We try to be good stewards of the land.”